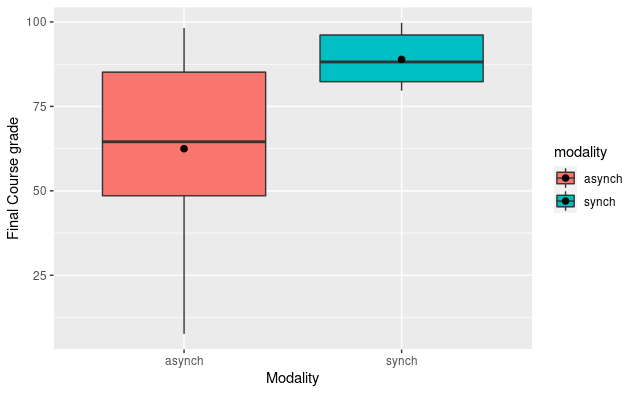

Last August, I wrote about the differing outcomes of the two Intensive Elementary French sections I taught: one remote synchronous, the other remote asynchronous. My write-up included some descriptive statistics, and ultimately concluded that learners in the synchronous course achieved higher scores than those in the asynchronous course. At the time I wrote the post, my statistical literacy was less than it is now, so the purpose of the present post is to determine whether these findings were statistically significant.

I. Do final course grades differ between the two modalities?

I took the two sections, asynchronous (n = 19) and synchronous (n = 10), and conducted a two-sample t-test to determine whether there is a meaningful, measurable difference in the average final course grade for each modality. The data from each section were normally distributed according to visual testing and the Shapiro-Wilk test (asynchronous p = 0.12, synchronous p = 0.26). An F-test revealed that the data were not of equal variance (F = 13.66, p < 0.001, 95% CI [3.69, 40.01]). The Welch two-sample t-test revealed a statistically significant, large difference between the asynchronous and synchronous sections (t(22.49) = 3.87, p < 0.001, d = 1.29, 95% CI [-2.04, -0.53]). The observed difference in means was -26.46, with a 95% CI [-40.63, -12.29]. A post-hoc test revealed an actual power of 0.80.

As you can see from the visualization, the learners in the asynchronous course had a much wider spread of final grades, compared to the learners in the synchronous course. The huge, statistically significant difference between the modalities can be seen most glaringly: nearly 75% of the synchronous scores fall within just the fourth quartile of asynchronous scores.

Read the rest of this entry »